The headline in the Washington Post ahead of Nicaragua’s local elections hinted at skepticism: “Nicaragua Ruling Party Seeks to Expand Hold in Local Votes” (11/6/22). The story itself, taken from an Associated Press report filed from Mexico City, was worse, framing the elections as a “farce” carried out “under the absolute control” of the governing Sandinista party.

Why, one might ask, would the Post be interested in municipal elections in a small Latin American country, if not to support Washington’s attempts to discredit its government? The reality, that the elections again demonstrate that there is a thriving democracy in Nicaragua, has to be twisted into an argument that they represent a “consolidation of the totalitarian regime of Daniel Ortega.”

On Sunday, November 6, as a Nicaraguan resident for 20 years, I went to vote, and later toured various polling stations in Masaya, Nicaragua’s fourth-largest city. At the start of a new four-year electoral cycle, mayors and councilors were being chosen for every city hall in the country, from the smallest to the largest—the capital city of Managua.

Nicaragua has a well-organized system for supplying all those aged 16 or over with identity cards, which automatically put them on the electoral register. On polling day, 3,722,884 people were eligible to vote.

In the last general election, a year ago, 65% of registered voters took part. This time—not surprisingly, given that these elections were local—the percentage was smaller (57%). Yet it was still very respectable in international terms: Neighboring Costa Rica’s last local elections brought only a 36% turnout. Across the US, only 15% to 27% of eligible voters cast a ballot in their last local election. In Britain, turnout in local elections is usually about 30%, and only in Scotland have a few small districts seen turnout exceed 57%.

Reflection of success

Here is a summary of the provisional results. On the day, 2.03 million valid votes were cast. (Some 3.8%, or 80,000, were judged to be invalid or spoiled.) Of the total, 1.49 million (73%) went to the Sandinista coalition, and the remainder to opposition parties. The vote for President Daniel Ortega’s party was sufficient to win the mayoral vote in every district, although the makeup of each local council will depend on the proportionate split of the vote between parties.

In the national tally, the next largest share of the votes was that of the Partido Liberal Constitucionalista (PLC); its 256,000 votes represented almost 13% of the total. Four small parties took the remainder. There were four small towns where the total opposition vote exceeded that for the Sandinistas, but in each case, the vote was split between different parties, and the Sandinista candidate was elected as mayor.

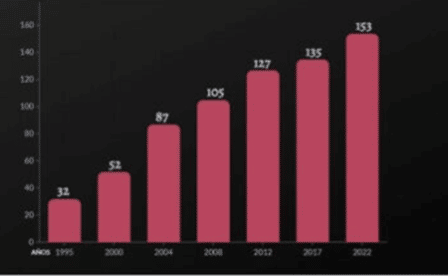

That the governing party nationally won all 153 mayoral posts was no surprise, since it had been making steady advances over the last two decades. As commentator Stephen Sefton (Tortilla con Sal, 11/7/22) reports, in 2000 the party captured the Managua council for the first time, together with 51 other councils. By 2004, the number had increased to 87; by 2008 it was 105, in 2012 it reached 127, and by the last election in 2017, 135.

Given that in the 2021 general election, the Sandinistas won 75% of the vote, Sunday’s result was fully expected. It reflects both the governing party’s success in stabilizing the country after the violent coup attempt in 2018, the enormous program of social investment it is carrying out (for example, building 24 new public hospitals in the last 15 years) and the country’s successful emergence from the Covid pandemic with less damage to its economy than neighboring countries experienced. The municipalities, which administer 10% of the national budget, have made important contributions to these efforts.

Of course, this is far from the image created by Ortega’s opponents. Brian A. Nichols, US assistant secretary of state for Western Hemisphere affairs, said before polling that

Nicaraguans will once again be denied the right to freely and fairly choose their municipal leaders. As long as opposition leaders remain unjustly imprisoned or in exile, and their parties banned, there is no choice for the Nicaraguan people in yet another sham election.

Unsurprisingly, he ignored the crimes committed by so-called “opposition leaders,” for which they had been tried and convicted. While a conditional amnesty in 2019 released from prison those convicted of crimes in the 2018 coup attempt, some who organized violence had begun to do so again in the run-up to the 2021 elections, or had been convicted of money laundering, or of actively seeking US intervention or sanctions. None of those “leaders” had ever run in local elections, nor were they members of registered political parties.

Ludicrous assertion

As is usually the case, reports in the corporate media followed the same line. According to the Washington Post, the vote followed “an electoral campaign without rallies, demonstrations or even real opposition.” Various other media used the same story—for example, ABC News (11/6/22) and the British Independent (11/6/22). Yet it was a complete lie: Scores of pro-Sandinista rallies and demonstrations had taken place across the country in the preceding weeks, as did far smaller opposition ones. The party that gained most opposition votes, the PLC, was unquestionably the “real” opposition, as it had held power nationally only two decades ago, and has won seats in all recent municipal elections. On the Caribbean coast, the regional Yatama party also gained more than a third of the vote in several cities and it, too, has recently held power.

As they did a year ago, the corporate media quoted the “evidence” supplied by an obscure body called Urnas Abiertas (“Open Ballots”)—cited in five of the AP piece’s 22 paragraphs. No one knows who this group is or where its money comes from. (Its website gives no clue.)

In a report quoted in corporate media, it claims that people queued at polling stations only because they were forced to vote. This relied on various messages allegedly from public sector officials urging their employees to vote—but of course if they voted, they did so in a secret ballot, and were at liberty to support one of five opposition parties, or to spoil their ballot paper. In any case, as I visited several polling stations, I could see that people were voting enthusiastically, not out of compulsion.

Oddly, in a claim that appears to contradict its main one, Urnas Abiertas also ludicrously asserts that a huge 82% of people abstained from voting and that “the streets were empty.” In an article for Council on Hemispheric Affairs (11/16/21), I showed that similar claims made after last year’s election were baseless. In any case, social media offered plentiful evidence of large numbers of people going to voting stations on November 6.

If the claim had been correct, it would imply that the government faked nearly 1.5 million votes. Urnas Abiertas fails to provide any evidence of how this was done, in an electoral process that is tightly administered, involves around 70,000 officials and where all the contesting parties have representatives scrutinizing each stage. Nor, apparently, did AP think to question Urnas‘ claims.

Washington talking points

Other elements of the AP report simply repeat Washington talking points. Apparently, “Nicaragua has been in political and social upheaval” since 2018, something invisible to people who actually live in the country. The government has “shuttered some 2,000 nongovernmental groups and more than 50 media outlets as it cracked down on voices of dissent,” a misrepresentation previously analyzed by FAIR (6/16/22). And “more than 200,000 Nicaraguans have fled the country since [2018], most to neighboring Costa Rica,” an assertion I debunked in an article for COHA (6/29/22).

Corporate media are so in thrall to the State Department’s propaganda about Nicaragua that they can’t ask simple questions: Could this election and the previous one mean that Nicaraguans really do endorse their government’s record? Why is Washington so exercised about a small country’s local elections? Is it that, once again, Nicaragua’s democratic achievements pose the “threat of a good example”? After all, in countries which claim to be superior democracies, a far smaller proportion of their electorates actually manages to vote. Instead of subjecting Nicaragua to ever-tougher sanctions, Western countries should ask whether they might perhaps learn something from a government that manages to win and sustain such a high level of popular support.